On a recent February morning, the street in front of the McMillan Memorial Library in downtown Nairobi, Kenya, took on a Victorian air. Shoeshine booths with high chairs and footstools—piled with polish, brushes, and buffers—bookended the library’s fifty-yard spiked iron fence, and young men hauled handcarts back and forth, loading and unloading goods for a few shillings a day. I half expected Mr. Pickwick to make an appearance. The library added to the feeling of being out of time and place: a pair of stone lions guarded a sweep of marble steps leading up to six granite columns and an oversize wooden door. The library was built in 1931, when Nairobi, now a heaving city of unambitious skyscrapers and four million residents, was just a few decades old and being fashioned by the British as a facsimile of London, but with better weather. A few hundred spottily tree-lined plots to the southeast, at the other end of Wabera Street, is the Supreme Court of Kenya, also built in 1931, and in a similarly grand neoclassical style. Together these buildings were the points of a high-minded colonial compass of the city: library and court, learning and the law. Though both buildings are still in use today, the court maintains an air of importance that the library lacks. When I visited the McMillan at ten-thirty in the morning, the front gate was chained and padlocked even though the library officially opened to the public at nine. The listed phone number didn’t work. “They have been closed all week,” explained one of the shoeshine boys. “Strike.” But there were lights on inside and the door was open a crack, so I hung around. Eventually someone stepped out and I beckoned him over. The young man pointed me to a rear gate reached via the expansive compound of the city’s Jamia Mosque, where, because it was Friday, a steady stream of worshippers was on the move. The heat of the late-morning sun, the honking of car horns, the call of the muezzin—all the chatter and chase of city life—were instantly dampened as we entered the cool quiet of the library.

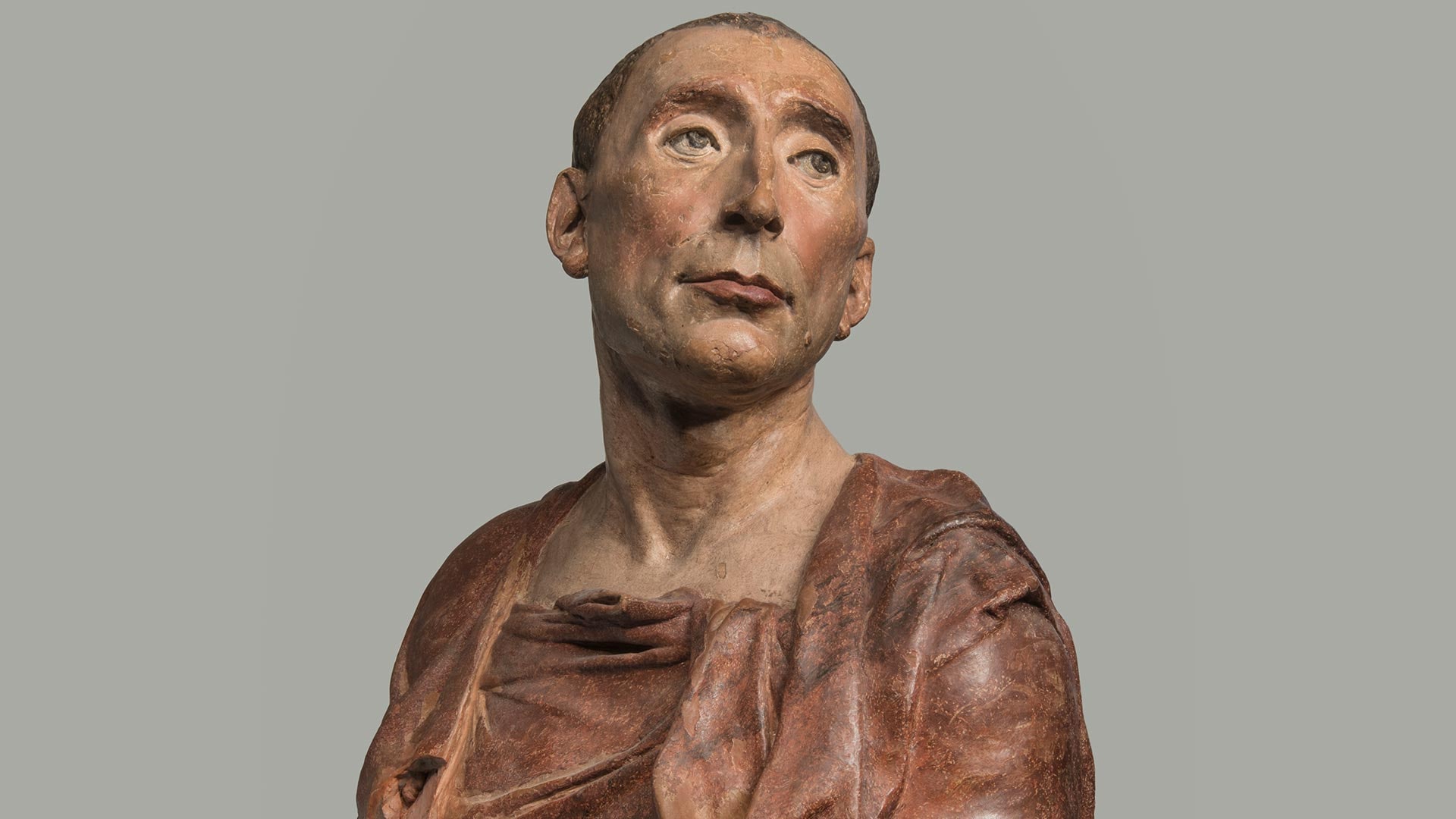

William Northrup McMillan was a member of the wealthy white adventurer set who made Kenya their home in the early 1900s, coming for the big-game hunting and staying for the cheap and easy land, swiped from its indigenous users. He was marked out, however, by being richer than most, thanks to an inherited fortune; an American among Englishmen; and a mountain among men: he stood well over six feet tall and weighed three hundred pounds. McMillan died while in France in 1925 and had his body willed back to Kenya, where he was buried outside Nairobi on a hill overlooking his farm and hunting lodge. Afterward, his widow, Lucie, commissioned the library in his honor, his name etched into the architrave in foot-high capitals and wrought in monogram in the transom window. For its first three decades the library was a whites-only institution. Finally, in 1962, shortly before independence, it was handed over to the city council and opened to the public. It was Nairobi’s first library and remains its largest. From the far side of the reading room, directly opposite the entrance door, McMillan’s sculpted head gazes sternly into the distance but is upstaged by a pair of immense ivory tusks. Nowadays, with the catastrophic collapse of Africa’s elephant populations, public displays of ivory are usually considered to be in poor taste, but inside the library the tusks are just another piece of historical bric-a-brac left where they are for want of a better idea. “We just found them here,” the chief librarian, Jacob Ananda, told me with a shrug. There were no more than a dozen visitors in the library that morning. An elderly lady in her Sunday best dress and matching hat transcribed sections of a Bible onto her notepad, a young girl with braids paged through a picture book of Austria, and five students hunched over coursework. One young man, hood up and head down, dozed while his smartphone charged in the wall socket behind him. Before sitting down, Ananda wiped a film of dust from the laminate table and our pleather chairs. The fifty-year-old has worked in Nairobi’s libraries his entire career and more than half his life, beginning as a cleaner, “dusting the way you saw me do.” As a recent high school graduate he had been led to expect a clerical job, but when he arrived he was handed a broom. It was the late 1980s and jobs were—then as now—hard to come by, especially for a young man from a poor family, so Ananda didn’t complain: “A job is a job. You start life. I got used to my work, because you have no choice.” While on his tea breaks he read, his tastes skewing toward social justice: Coretta Scott King’s My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., Chinua Achebe’s anti-colonial Things Fall Apart, and Nikolai Gogol’s satiric comedy The Government Inspector. In short order, Ananda progressed from cleaner to assistant librarian to chief librarian, which put him in charge of the city’s four public libraries. He earned a college degree in library and information science along the way. Taking me on a tour of the McMillan’s forty thousand books, Ananda insisted that the stacks were easy to navigate. We passed a jumble of social sciences, a wall of languages fencing off a disused children’s reading room filled with drifts of abandoned chairs and shelving units (“renovation,” he said), and a shelf of oversize books hidden behind an unmoored bookshelf of science. We continued toward the flotsam of fiction and leaning shelves of biography, all with little in the way of signposting. Periodicals, academic books, and fiction make up the majority of the McMillan’s holdings, much of which dates back to the library’s founding or its better-resourced early years. The collection has a take-what-you-can-get feel about it now: Ananda cannot remember the last time he was able to save any of the meager $30,000 annual operating budget to make new acquisitions. Upstairs in the reference room, geologic forces were at work: stratified layers of leather-bound newspapers, standing five feet tall and dating back decades, crumbled at their lower reaches onto the parquet floor; tables had become subduction zones of books. There were glass cabinets containing dust-clad editions of Pliny the Elder, Theodore Roosevelt (who visited McMillan at his farm and joined him on hunting adventures), and Washington Irving. The ceiling was water-damaged, and oil paintings of McMillan, his wife, and a collection of nameless old men with mustaches and extravagant sideburns were propped against walls. (“Buddies of McMillan, perhaps,” Ananda said.) We walked along an upper terrace, exposed to the outside but hidden behind the building’s columns. A moth-eaten, taxidermied lion’s head with the stuffing coming out its ears rested on a table en route to the Africana section, where imperial histories and colonial adventurers’ memoirs and biographies dominate. The library’s past explains its neglect. “We inherited this from the white settlers; it was not for Africans,” Ananda said. When control switched to the city council, they showed little interest in investing in a racist institution named after a rich American. But time has softened attitudes, and the library is undergoing a fitful rebirth as something other than a historical artifact. Last year, a Kenyan cultural organization called Book Bunk—founded by the writer Wanjiru Koinange and the publisher Angela Wachuka—signed an agreement with Nairobi’s governor to restore and revitalize the McMillan and two other city libraries, to make them into places where Kenyans will come and find books that speak to them. Book Bunk has crowd-funded $6,300 to inventory and catalogue the Nairobi libraries’ collections and is working to establish a program of public events to draw visitors to book launches, readings, homework clubs, screenings, and talks, and to begin the process of acquiring books that better reflect contemporary Nairobi. “We need to Kenyanize, if not Africanize, the library, because the stock is as old as the library! You can see a book that has been here for the past eighty years, it is not relevant,” Ananda said, gesturing to the shelves, where it was easier to spot a 1973 guide to the English county of Shropshire (last checked out forty years ago) than a novel by a Kenyan author. It needs to modernize too: there are neither computers nor Wi-Fi; books are found by scouring the shelves or searching through the drawers of the old card-catalogue system. Outside support is essential, Ananda said, because in city funding battles with schools, hospitals, or road maintenance, libraries lose out. Though he has been coming to work here for decades, Ananda remembers clearly his first visits as a young man, when the light from the brass chandeliers kept the gloom of Nairobi’s dank cold season at bay. As he stepped inside the imposing building, he said, he was transported to a place of history, erudition, and solemnity, a reprieve from the helter-skelter modernity outside. “The library was at its best,” he said, smiling at the memory. “Now we have leaking roofs. At times we feel sorry because you long to make it be a better place.” Tristan McConnell is a writer and foreign correspondent who lives in Nairobi. Africana room, McMillan Library, Nairobi, 2019. Photograph by the author