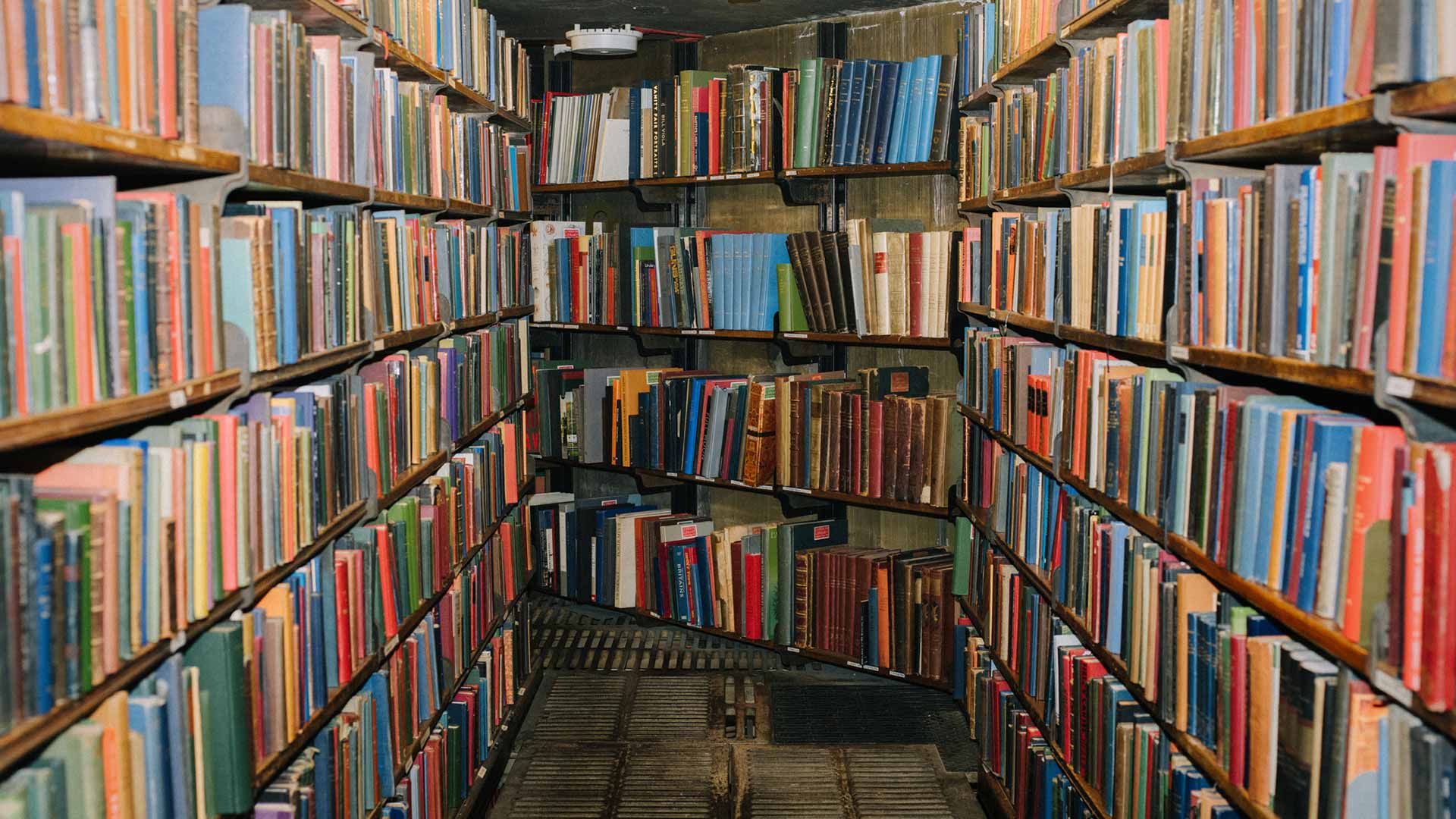

The versicolored stamp admitted you to a new country. But once in that new country you had no guarantee of returning to the old one, the country of your childhood. All because you (your parents) hadn’t acquired a different versicolored stamp when you were small. You told yourself that you weren’t going to think about that, but the fear of being unable to return to the only home you knew nibbled away at your sanity. You had always prided yourself on being able to whip the mind into discipline—so it shamed you to realize that your Oxford supervisor, whose learning threatened to overwhelm you in tutorials, had concluded you were a mediocrity. The pointy bones of his criticisms came wrapped in sleek Oxonian fat. Something was wrong. You checked yourself into a hospital and were told that you needed to sleep more. You turned to self-medication: long walks, fits of bibliomania, the humorlessly persistent consumption of port. You stopped brushing your teeth. You noticed how unpleasantness began to emanate from you like bad breath. After three bottles of wine one night, someone got a strong whiff of the stench. You were sitting in the graduate common room watching TV with the only other brown-skinned classicist. Suddenly you just flipped out on her, started tripping: “You don’t know me. You don’t know who the fuck I am.” How embarrassing. The next day, you went on a walk to see some cows in a meadow. Real bucolic shit. Then you called to apologize. *** You briefly indulged in a little introspection: enough to conclude that the main cause of your little outburst was frustration at being unable to head back to the United States. You reasoned with yourself: Even if I can’t travel to America, I can travel to so many other places! Let’s do that Tennyson thing—drink life to the lees, ball out. First stop: France. Arrête: since you are brown and originally from a country of browns, you are not credentialed to float into France on the strength of your passport alone; you have to deposit your corpulence in a chair at the Consulate General in London in order to secure the Schengen visa. Early one weekday morning you took the train to Paddington Station and the Tube to South Kensington. You joined the ranks of brown and black faces, were ushered in, crammed yourself into a seat. Your life in that other country now denied to you had supplied years of instruction in how to spend hours in under-ventilated rooms while bureaucratic gears turned: you came prepared with an Ian McEwan novel. (Was it Amsterdam? Atonement?) About two hundred pages in, you were interrupted by the mangling of your name in French. You proceeded to a window to be quizzed by the consular official who was thumbing through your stack of papers. “So you are from the Dominican Republic?” “Yes.” “I’ve been there on vacation. Beautiful country, and the women”—pause for the knowing glance and wink—“très jolies.” Oh yes, you felt the rush of rage again, except this time there was no alcohol: only you, perfectly sober, wanting to duff this dude in the face for making use of his French passport (which empowered him to go pretty much wherever) to travel to your country. Wink-wanker was a sex tourist. What did you do? Nothing. Even worse: you nodded at him, he smiled, you took back your stack of papers. An hour later you walked out of the embassy, passport and Schengen visa in hand. Another long walk. Then you met up with London friends. This time, no drinking for you. *** Congratulations, you made it back to America! Work visa, “waiver of inadmissibility.” You were quarantined on your return flight from England: you pressed your thumbs down on the biometric device and handed over passport and visa to be scanned, and the immigration officer pointed you to a special holding room at JFK. There you waited with other blacks and browns, and a white couple who’d lost their passports while traveling. These couples could always be trusted to wail: “But we’re American! Why do we have to keep waiting?” You (and the other browns) knew better: kept that mouth shut right until the officers with the look of fatal boredom called you up to the front of the room. Now, you wanted to finish your schooling in the States, get that Ph.D. And did you know that you had to have a different visa status for that? Well, now you knew, and it was time to file another application. Pro: no visit to an embassy required. Con: no idea whether or when the application would be approved. The lawyer you’d been working with for years was not exactly sanguine about the prospects. A month became three, and three became six, and still nothing from the sovereign lords at USCIS. You got antsy. One night you were visiting friends in D.C., had one too many shots, got into some back-and-forth at the bar with a lacrosse bro. Did he say some racist mess? The N-word or something else? You don’t know: you were too faded. You remember confronting him, trying to fight him in the men’s room (who tries to throw down in the men’s room?), being dragged away. You bused back to your parents’ place in New York and told yourself bien serio to cut that out: fighting lax bros was a great way to get deported. What was eating you? Having to deal with bureaucracy? Bureaucracy is life. Grow up. Drink less. *** Scraps of paper finally came in the mail. For a moment you really did allow yourself to get excited! The Stanford doctoral program was going to happen. You looked at the stamped and signed sheets, you turned the pages over very gently, you smiled. But within minutes the initial excitement ebbed and vanished. To think that your life had been put on hold for these numbered flimsy hojitas of paper; talk about anticlimactic. Good little classicist, you turned to texts to make sense of your feelings. Seneca? Butt-kissing hypocrite. Epictetus? Too dour. Marcus Aurelius? Too whiny. Other texts more in harmony with your paper-pushing crisis entered unbidden into your mind, crowding out the Greeks and Romans. Edward Said, holding forth on “the new post-colonial international configuration” whose architects “seemed to require borders and passports first of all”: “a world system of barriers, maps, frontiers, police forces, customs and exchange controls.” Leela Gandhi, feeling for the pulse of “that perverse psychic condition which makes us homesick for those places in which we were foreign.” Yet in the end there were no words out there just for you. No words to free you from craving new documents; no words to liberate you from the fresh resentment the need to acquire them inspired. All you had was fleshy recall, summoning you back to precincts of muted pain.

Documentary Anxieties

Dan-el Padilla Peralta is Assistant Professor of Classics at Princeton University. He is the author of the memoir Undocumented (Penguin, 2015) and co-editor of Rome, Empire of Plunder (Cambridge, 2017).