From his early, unclassifiable beginnings alongside Peaches in late-Nineties Berlin to his elegantly pared-down trio of Solo Piano albums and work as a producer on Feist’s breakthrough album Let It Die, Jason “Chilly Gonzales” Beck has for years been a maestro on the keys and a go-to collaborator for an international who’s who of multiplatinum stars—from Daft Punk to Drake to Jarvis Cocker. Yet the core of his output remains electrifying live piano performance, sometimes with backup instrumentation, sometimes with punchy lyrical excursions, always in a bathrobe and velvet slippers. In 2017, he began devoting his time, resources, and industry connections to an ambitious new venture he calls the Gonzervatory: his own music school and all-expenses-paid residential performance workshop that culminates in a public concert in which he conducts his students. It did not seem unfitting, when I visited him late last spring at his apartment in a leafy section of Cologne, to find that he lived right off Beethovenstrasse.

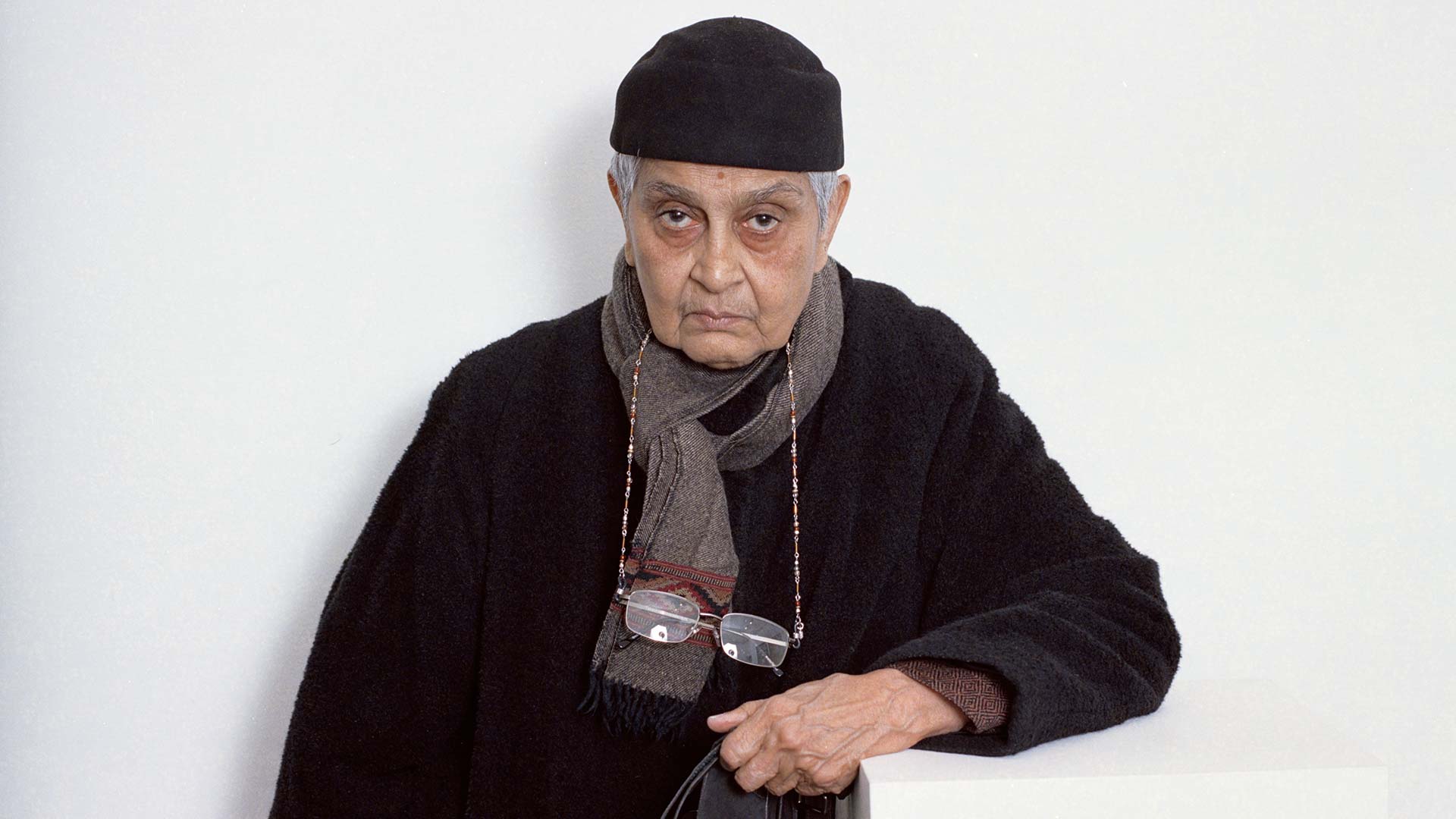

Chilly Gonzales

** What kind of music do you listen to at home? I don’t listen to much music at home. But if I’m out walking or traveling, I find rap really engaging. It reminds me of reading comic books as a kid, in that there’s a lot of crossover, this rapper working with that rapper. It’s a bit like opening up a new issue of the X-Men every week for me. Go on Apple Music or DatPiff and see what new tapes are there. You go on DatPiff? That’s where you get some stuff that wouldn’t be on Apple Music, because it hasn’t been properly licensed. I might not listen to one of those tapes for longer than a couple of weeks, when it’s slipped from everybody’s consciousness and gets replaced by someone else’s mixtape. Rap is not the kind of music for me where there are so many classics that get added to my collection and never leave. It’s much more ephemeral. It comes and goes, like issues of a comic book. You’re actually a pretty deft lyricist. How did you teach yourself to rap? I never thought of it as teaching myself. When I moved to Europe—and this is for better or worse, because things have shifted now, in terms of how people talk about cultural appropriation—it was the early Aughts, and we had just sort of gotten over the political correctness of the Nineties. There was Eminem and Sacha Baron Cohen and it was okay to … Play with another music scene? Exactly. When I moved to Europe, I could suddenly feel free from the question of “Should I or shouldn’t I?” and I was able to just say, “Well, it seems like here in Europe, rap is seen as a musical style, and is perhaps separate from hip-hop culture.” I’m someone who always tries to see the commonalities in music. Focus on what unites humans rather than focusing on the differences. There are some fundamental things that are just natural to music itself. Or at least to Western music. I always wondered, “What if a style of music wasn’t limited to its culture? What if a style of music wasn’t limited to its technology? What if a style of music wasn’t limited to its usual audience?” Did you just figure out how to do it as you went along? I was always into words. As a kid, I realized that there was something with the way rappers used words, and the playfulness and the conceptual self-actualization of the form. What inspired me the most was that rap didn’t seem to have to choose between being serious or silly, it could be both at the same time. I was always being told, as a musician, I should choose my camp. But rap could be enlightened and ignorant at the same time. It could contain all these contradictions. But I’m very sensitive to the cultural appropriation issue now. Maybe that freedom that I felt to essentially try anything, musically speaking, and look for those commonalities, could be seen as an act of erasure, as well. I’m cognizant of that. There doesn’t seem to be any perfect answer. I’m staring at the “Marvins Room” plaque from your collaboration with Drake. You have worked with some really important rap artists.

Drake came and saw my show, and he wrote me a Twitter message saying, “You rapped your ass off tonight.” That’s a nice compliment. Am I supposed to mention it onstage to get more credit? No. I think the solution is just to do it, not to question it. And if some people think it’s corny, they think it’s corny. There are also lots of other ways to show my love for that music without necessarily having to be the one to rap. That seems to cross a line for some people. Whereas to have it as a musical influence in my chord progressions doesn’t seem to many people like an appropriation. You have an extraordinary stage performance across the board. Solo Piano (2004) was an epiphany for me. As a child, I took some lessons, but if somebody had shown me that the instrument could be engaged that way, I would’ve been a much more serious pupil. Your professional beginnings with Peaches in Berlin in the early Aughts were extremely experimental and very far away from this kind of polished sound. Yet it seems like you came out of Berlin fully formed as a concert pianist. How did you make that sudden transition? What couldn’t really be seen from the outside was that I was still searching in Berlin. The Peaches world is a part of me. But I was missing another part. And I didn’t know how to reconcile those two parts yet. That’s why the shift, which is dramatized in Shut Up and Play the Piano, probably seems so extreme. But it’s still all music. So you were always practicing? Not quite. I couldn’t afford to have a piano back then. But for the first three or four years I played as a day job in different traditional restaurants in Berlin. I’d done that in Canada before I left. That’s how I supported myself. You were really hustling. My dad’s a businessman. He took over his father’s modest European construction company and turned it into an infrastructure company. He’s this workaholic, immigrant type. He never really fit into the establishment and always kept this Hungarian, Jewish, hustler mentality.

One of the reasons I think I like rap is because it reminds me of my dad’s work ethic so much. He’s definitely a get-rich-or-die-trying guy. As I often say when people ask me about rap: I’m more the son of a rapper than a rapper. I’m much more Jaden Smith than Will Smith, let’s put it that way. You modeled your Gentle Threat record company off the idea of being more like a rap imprint. Well, it’s entrepreneurial. Entrepreneurship mostly existed in electronic music and rap spaces. In both those worlds, a lot of people have their own labels. I mean, my buddy Tiga, in Montreal, had a label already back in 2001. Now it’s what everybody does. And that’s not normal in classical music? In classical music, not at all. I approach the business as a pop musician. My only connection to classical is that I play in those venues.

In genre terms, then, how would you describe the Solo Piano series? It’s pop music. It just happens to be on the piano, and it has a bunch of classical colors and jazz nuance, but fundamentally I don’t think of it as those kinds of music. The songs are all short, three-minute pieces. I think of them through a pop music lens. I’m not interested in being in classical magazines or having that respect. That’s not what I’m chasing at all. Getting to work with Drake or Daft Punk or Jarvis Cocker is much more exciting for me. It proves my hunch that people can hear the pop in my music. People can hear the rap in my music, or the electronic in my music. And then [another artist might] think, “Oh, we would like to have piano!” Although a track like “CM Blues,” I’ve listened to that track thousands of times, and it’s not pop music. Well, it’s the restraint and the reduction of jazz or classical elements. And that’s what also makes it pop. Because pop is about reduction, and one or two good ideas. That’s exactly why it’s pop music. There’s no solo. I remove, literally remove, the number of notes. I make the rhythm much more static. In real jazz music and real classical music, the rhythm is fluid, it’s much more expressive and unrestrained. There tends to be a lot more virtuosity. They tend to want to put in more notes, because there’s a higher premium placed on technical ability. There’s no premium on technical ability in my recorded work. In the live show there is. Sure. That’s almost coming with some irony, as well. But on the recorded work, it’s reduced. It has the aesthetic of pop music, which is reduction and repetition. That’s why, in the end—it’s not false modesty—I wouldn’t fit into the jazz world, because I’m repulsed by indulgence. Really? Yes, very much so. To me those are crimes against music, when the musician puts himself first. The music should flow through you as a vessel. That might seem counterintuitive given my big personality and the fact that I play a megalomaniac onstage. But the truth is, anyone who knows me and works with me sees what a humble servant of music I am. There is a very goody-two-shoes side to my musicality. A lot of respect for the music that came before me. I tend to like music with melody—music without a melody is just atmosphere. Which puts me at odds with a lot of music-making today.

Music should be very direct, straightforward. It should please people. It shouldn’t challenge the listener too much, except in ways that reward them fairly quickly for their patience. Therefore my songs tend to be short and digestible. I think with the ears of the audience in mind. How do these ideas come to you? Do you wake up and you have melodies or rhythms or songs brimming in your head? Sure, but it’s mostly from just sitting at a piano, whether it’s at sound check or at a friend’s house or here. You just play around? I do it every day for an hour or ninety minutes. Just play. You generate ideas that way?

Being a working bar pianist gave me the humility to understand that there’s nothing wrong with background music. But a concert is a concert. And, as you see, I’m not acting like I do in the concert. I’m not in my persona right now. But you are in slippers! It has its place. A concert is supposed to be exciting, to grab you. Having a persona onstage engages people, in my case a little bit through humor, a little bit through trolling, and a little bit through shocking, but also through a more genuine musical inclusion, with the teaching I do and telling the stories behind the songs. Did you have to work at achieving this persona? I had an instinct for it. But of course I’m still working on it. I’m fascinated by stand-up comedy. You realize that with just one little pause, or a little change in the order of words, you get a totally different result. Over the course of doing forty shows, over six months, I’ll understand, finally, “When I do the Bach routine, now I know the best way to end it.” I love the stuff you did with Feist. I’ve watched quite a lot of your performances on YouTube. Live performance is my work. Everything else is secondary. Albums are secondary. Concerts are what I was born to do. They are what I love and what I’m good at. It also happens to be what pays the most. The music industry has headed in a direction that’s been extremely beneficial for performing musicians who know how to use the Internet. Many other musicians, who really do prefer the studio, and who begrudgingly play live, it’s really hard for them, because they wake up in the morning thinking, “I don’t want to go.” It’s the happiest day for me when I wake up and I have a show. You don’t have any stage fright? I have stage fright in the sense that it’s super nerve-racking to get up in front of two thousand people. Something would be wrong if I didn’t. But I know how much I enjoy playing, so that makes it bearable. Whereas for some people, it is really crippling. And I think if you don’t really enjoy being onstage, the nerves are so bad that you’re thinking, “Why am I suffering?” As a writer, what pays well is going to a college where the freshman class is doing your book and you give a lecture to a thousand kids. I will never enjoy that the way you look like you enjoy playing the piano! Yeah, but music is performance. Writing isn’t performance. In addition to performing, I wonder also about the teaching. What is it about teaching that is so much a part of your practice, as well? You seem to love not just selfishly having a talent but eliciting talent in other people and drawing it forth. Where does that come from? I’m not sure. But maybe because I grew up really privileged and I feel like music gave me so much, so, it’s probably good to not keep that all for myself. The Gonzervatory is a passion project. I wouldn’t say it’s selfless, because I get up in the morning and I’m excited to be doing it. It has the effect of the energy spreading outward, rather than only inward. Music always seemed like a toy to me, and so it’s a little bit like if you’re a kid again who wants to share his toy ... Well, some kids don’t want to. Those are not nice kids.

If you’re a cool kid, you want to share your toy and show what you can do with it. “Look what my toy can do, and look what I found out! And if you take it apart, look what it does!” I feel like that’s what I’m doing with the Gonzervatory. My skill set normally would have me existing in a more classical, jazz, or academic setting, but it just so happens that, growing up with MTV in the Eighties, I had these pop fantasies in my head. I wanted the pop fantasies to also reflect the other, respectful side of music that my grandfather was showing me as my first piano teacher. Was he talented? I’m not sure. He died when I was in my early teens, so it’s hard for me to remember what his talent level would’ve been. But he certainly had enough passion for it to pass on to me and my older brother, who is a professional musician. Your brother, Christophe Beck, composed the Disney movie Frozen, right? Well, he composed the score for Frozen, yeah. He did not compose the song that your daughter probably sings. That’s the biggest movie in children’s entertainment ever. Pretty crazy. My grandfather coexisted with this other world of, “Look, Lionel Richie looks so cool dancing on the ceiling!” I’m still trying to have it both ways. I’m still trying to maintain that more conservative, respectful, priestly side through the diligence and hard work and teaching—really seeing music as something that is akin to a lifesaving force for people. Treating it with that heft that it deserves and the humility it deserves. But I also wanted to exist in the pop world and I know that humility is not what’s needed there.

I reinvented myself, taking some pages from old-school entertainment and studying the history of vaudeville and getting interested in comedy, interested in rap, interested in all the exciting, playful entertainment-oriented people who inspired me. Even including some self-help gurus. My interests were always communication and framing. Sometimes you want to frame by doing nothing. Sometimes you want to frame it by speaking. Sometimes you want to frame with body language. Sometimes you want to frame with lighting. These are the kinds of things I teach at the Gonzervatory. It’s performance theory and audience psychology. I wanted to ask you about being an expatriate. What made you come to Europe? It was clear that the music I was doing was something that would do well in Europe. And I was really struggling in Canada, at the time. Even though you came up with Peaches and Feist? Yeah, but that happened in Europe. We were kind of a gang of musicians. There were seven or eight of us who were doing music in Canada, but we were very frustrated and feeling like, surely what we’re doing is interesting enough that we should have a little bit more encouragement. So in the summer of ’98, we took various trips and discovered Berlin, where Peaches and I ended up. That’s an amazing time to have arrived in Berlin. We saw our bohemian fantasy come to life. We arrived in July and I moved there that September. Peaches followed in December. And then other people started following. Some went to London or Paris. But many musicians I knew were converging on Europe. How did you end up in Cologne? Mostly for personal reasons back in 2009. I like Germany a lot. Do you see yourself staying here now? Or could it change again?

I’ve been here for seven years and I have a good, healthy lifestyle here. I can treat myself better than anywhere else I have lived. What is the scene like here? Luckily, I’m beyond needing to be in a scene. Because of my age, because I already have a foothold in the music world, and because of the Internet, I don’t have to be in the center of the action. Also, I’m in Paris every two months. I’m in London every month. But Cologne is a nice place to come back to. It’s a city for just the music side of me. The career side of me doesn’t really exist here. What are your routines here? I’m walking a lot. I read novels. I take naps, I hang out, I have a social life, a personal life, it’s great. And when I work, I really work. You’re just Jason in Cologne. Pretty much. The Gonzervatory is here, so there are moments where the Chilly Gonzales spirit does come on strong in Cologne, but not in my daily life. I like that separation. Compared to when I was living on the rue des Martyrs. Paris was getting to be too much? Why have a stressful day-to-day life when my work already involves so much travel stress? Was it stressful to be recognized in Paris? No, but don’t you realize what a stressful city it is? It’s extremely stressful. Coming from New York, it feels quiet to me. Spend a week here and you’ll see what it’s like to chill. But it’s still a city. A lot like Montreal, now that I think of it. I’m from Montreal, it’s a similar size, similar level of chill.

You produced Let It Die, by Feist, which is one of my favorite albums. There was something you said earlier about the life-affirming quality of music. I was raised on hip-hop and black music. And there’s really nothing black about Feist, but there’s something that just transcends any category. The aesthetics of the production are very much like the Neptunes, and Feist’s own singing owes a lot to early folk music. Alan Lomax—she’s so into that. Her rhythmic intention, when she plays guitar, is very influenced by blues people. There’s soul in it. She came by it honestly. It’s not an academic exercise. Musical styles don’t exist in a vacuum. They are connected to cultural movements. That’s a beautiful thing. But I don’t try everything. I’ve never tried reggae. I’ve done collaborations with lots of other musicians, which lead people to think I’ve done those styles. There is something so universal about all of the music you touch. You and Feist seem like one of those collaborations that doesn’t come along very often. How did that happen? When we first met, she came on tour as the Chilly Gonzales sidekick, and then very, very slowly she began writing her own songs. She once said of that early time that she wasn’t sure what her talents were and you didn’t know what you could offer her. I liked the songs she was writing but I could see she was really stressed out about them. I thought she was such a great singer that we should do some cool covers that no one knew. I co-wrote, arranged, and produced. But she’s a complete artist, and essentially always has been. How did you start making the album?

I met someone in Paris who had a studio and was a good engineer and potential producing partner. We had some days off. Were you surprised by the product and how much it resonated? You never expect a breakthrough. Otherwise, you’re jinxing it. It was clear that Feist had a lot of talent, charisma, and ability to connect with people. I don’t feel like I did much, except just not fuck it up.

Thomas Chatterton Williams is the author of Self-Portrait in Black and White and a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine.