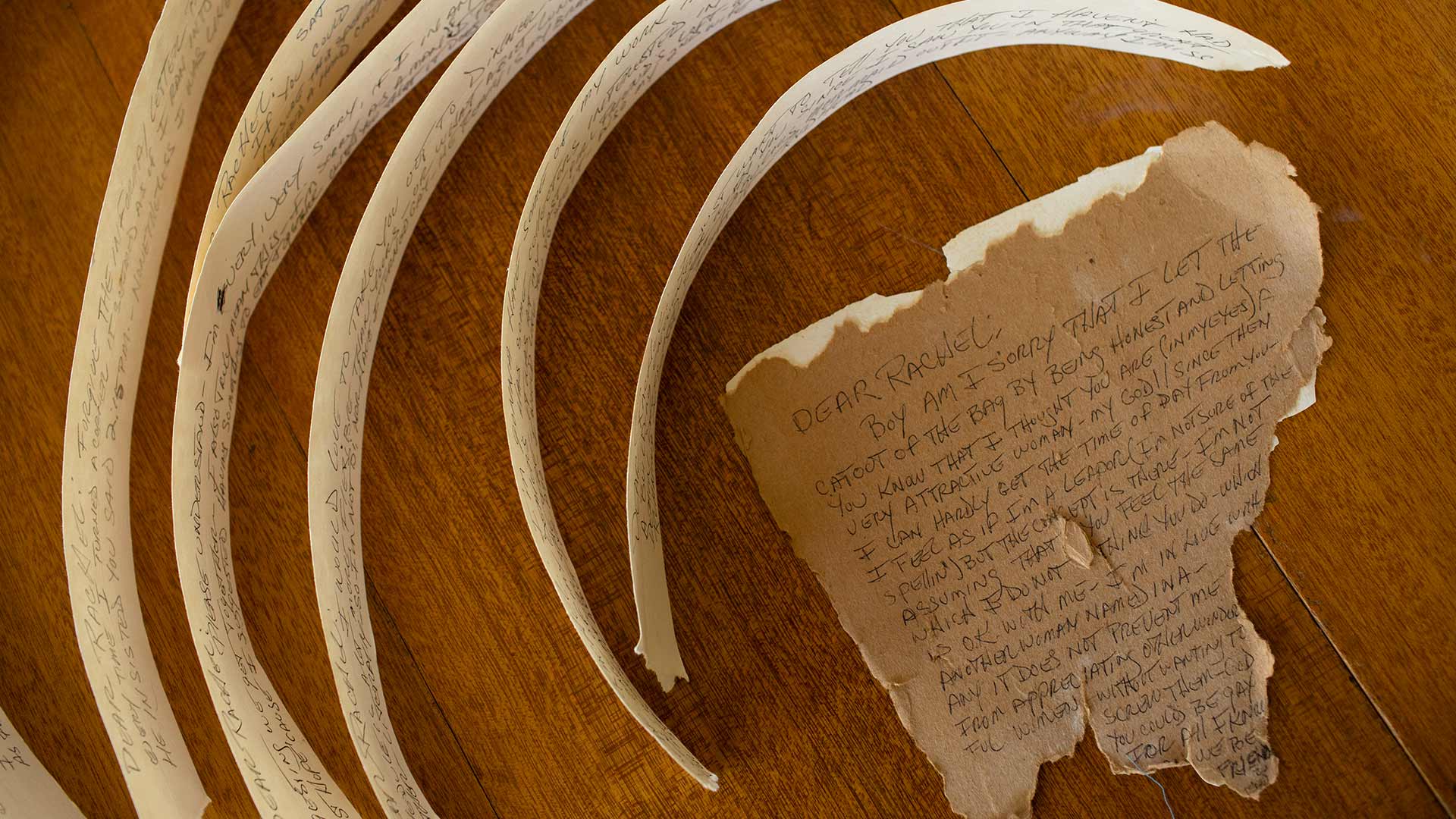

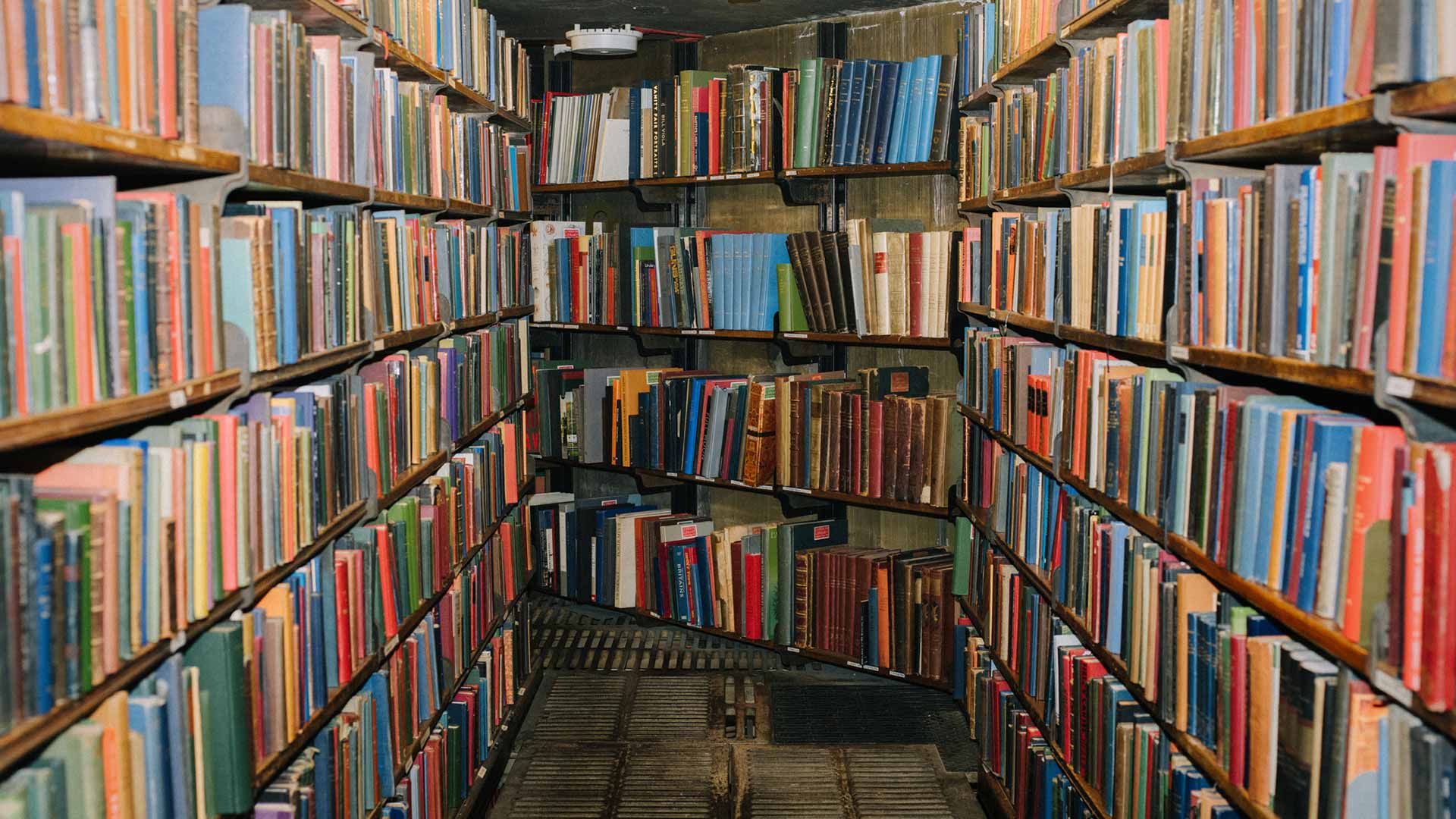

Duncan Hannah is an American painter and collagist who has had more than fifty solo shows in the United States and Europe. For decades, he has also been a well-known New York figure, with a seemingly limitless supply of stories about his adventures among the famous and the infamous in the highest and lowest realms of the city. This month, Twentieth-Century Boy, a volume of his diaries from the 1970s, is being published by Knopf. I visited Hannah in his studio in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, a large, light-filled space with a chandelier, floor-to-ceiling books, and a plywood table on sawhorses. Over many cups of coffee, we discussed his life as a young beauty on the make, a sexual explorer, an underground archaeologist, and an aspiring artist finding his vocation. You didn’t look at these diaries for twenty years, right? More. I never read them—six feet of journals. What finally happened was, I’ve got a friend who works for [rare-book dealer] Glenn Horowitz, and he saw them and said, You know, we could sell this. I thought, Oh, fuck, I should read them first, at least. And I should mine them for natural resources, because I have no idea what’s in there. So in the spring of 2016, I stopped painting, I got Microsoft Word—I think I got a new laptop, even. I started with the first intact one, winter of 1970, because I thought, Okay, that’s good, it’s a new decade. But really with no ulterior motive other than to keep a copy of something I was going to sell. There was all this LSD drivel, just stream of consciousness. And then there’d be a nugget of a funny story and I’d go, Oh, that’s good. Some of it I remembered, some I didn’t, but it did start to come alive. The list of people you wrote about is amazing. I guess, right off the bat: Lou Reed. Was that the first time you met him? And the last. I mean, I’d see him around, but he didn’t recognize me. But that song, “Rock and Roll,” I first heard it on an FM station in Minneapolis, driving in my car, and it was an epiphany. Euphoria. Such a rush. So when I saw him at Max’s Kansas City I thought, That’s the guy! What happened was a great lesson in the dangers of hero worship.

The Hotel Duncan

Duncan Hannah

What happened? There was this small room downstairs with a velvet rope, so you had to stick your head in and see if somebody waved you over. I was sitting with [Stooges and Ramones manager] Danny Fields and Fran Lebowitz, who was nineteen and just the same as she is now, funny and grumpy. She got up to leave and Danny said, Louis! Louis! So Lou Reed came over, Danny introduced me, and he didn’t pay any attention. He started talking about this and that, he wanted to kick Lester Bangs’ balls in, he’d just seen Peter Wolf and Faye Dunaway fucking at the Chateau Marmont while he was with Iggy, he’d just auditioned the MC5 drummer for his band, you know, just kind of Lou Reed stuff. Then he started talking about Raymond Chandler, and that summer I’d read all of Chandler. I thought, Oh, I can talk about this. So I said, “Yeah, I love that, and that bit he actually cribbed from Hammett, except it wasn’t in The High Window, it was in The Little Sister.” And this just stopped Lou in his tracks and he said, “Danny, she’s talking.” And Danny said, “Yeah, she talks.” I felt chastened, so I shut up and he went on, and then I did it again, I said, “Oh! I know! And then there’s that great switch!” And he said, “Danny, she’s doing it again.” And Danny said, “Well, she’s a big reader.” And he said, “Where did you find her?” “I found her at the Waldorf. The New York Dolls had a Halloween party.” And I was thinking, Okay, so they’re talking about me like I’m not here, A. And B, I’m a she! And I thought, Oh, well. What do I know? This is their clubhouse and I’m just a visitor. I’ll see where this goes. And where did it go? Danny got up to get cigarettes, and “Walk on the Wild Side” came on and I said, “Hey, do the ‘doop-de-do’s with me!” And Lou Reed said, “Are you fucking kidding me?” And I said, “No, come on.” So he started doing it! We were going, doop, de, do, de, do …” And then he just started laughing, like he was incredulous. Then he said, “You look like David Cassidy. Do you like David Cassidy?” And I said no. And he said, “I do.” And he said, “Do you belong to Danny?” And I said, “No, Danny’s my friend.” And then he said, “I’ll tell you what. I have a hotel room nearby. Why don’t we go there and you can be my little David Cassidy? Would you like that?” And I said no. And he said, “Well how ’bout this? We’ll go there and you can shit in my mouth. Would you like that?” And I said no. And he said, “How about I’ll put a plate on my face and you can shit on that and then I’ll eat it? How would you like that?” And I said, “Yeah, I wouldn’t like that.” And then he just stared at me and said, “You’ll be missing me tonight,” and left. I was just sitting there thinking, Wow, that was so not what I thought was going to happen. Then Danny came over all excited and said, “Lou’s in love with you!” I said, “How do you know?” He said, “I just saw him in the men’s room—he told me.” I said, “You know what he just asked me to do? He asked me to shit in his mouth!” And Danny said, “Didn’t you want to?” And I said, “No! What’s wrong with you people?” So that was my introduction to Lou Reed. He was going through a bad time, I guess.

Do you want to tell me about meeting Dalí? It was such a funny story but I was confused about the end. There is an end to it, which I couldn’t put in, because I heard about it ten years later. I was at an Interview magazine Valentine’s Day party, and I was really drunk. Amanda Lear, who was Bryan Ferry’s girlfriend, came over to me. She was blond, looked like a European movie star, and she sat next to me and started scolding me, “Dahling, you’re so drunk.” Anyway, she was part of Dalí’s entourage and would I model? I said, “Sure,” in my drunken way. A week later she called and said, “Meet me at the St. Regis and you’ll meet Dalí.” So we’re having a drink in the Old King Cole room and it was happy hour, so it was crowded with tourists and wealthy businessmen, and suddenly in the doorway in a gold cape was Dalí with his eyes bugged out and his crazy mustache. And the noise in the bar went down. And then he proclaimed, “Dalí is here!” And it went silent. So he strides over waving a cane around, completely preposterous. And Amanda says, “This is Duncan Hannah.” So he sits down next to me and says, “Yes! So you are going to be an angel for Dalí.” And I said, “Sure.” And then he said, “But wait! Do you have hair on your chest?” And I said, “No, I don’t.” He said, “Ah, this is good. Dalí does not paint angels with hair on their chests.” And then he said, “But wait! Are you a professional model?” And I said, “No, I’m not.” And he said, “Ah, good! Because Dalí does not paint professional models.” And then he said, “But then what is it that you do?” And I said, “I’m an art student.” And he said, “Ah! Then you love Dalí!” And I said, “Oh, yeah, we’re all crazy about you down at art school,” which was a complete lie because everybody just thought he was kitchiest, worst painter ever. Then Amanda took me up to her room. She was changing for dinner and it was dark and she was toying with me like a cat with a mouse. She gets down to her underwear and I’m thinking, What’s going on here? Then the phone rang; it was Bryan Ferry from Toronto, and I just adored Bryan Ferry, and I could hear him saying, “Who’s there?” “Oh, just a beautiful boy …” And he’s going, “What beautiful boy?” And I was thinking, Bryan Ferry’s jealous of me, yay! But then she had to go, Rod Stewart was sitting in the lobby. She called the next Sunday and said, “You have to come up to my room to watch The Ballad of Cable Hogue.” I said, “Sorry, I have to do my homework.” And she said, “This is Amanda, baby. When Amanda snaps her fingers, you come.” And I said, “I know, but I still have to do my homework.” Then she got really mad, saying, “This is it, unless you get up here right now”—which seemed like stud service—”you can forget about modeling for Dalí!” So I said, “Fine, I’m not coming.” Bang! So anyhow, years later I had a new friend who was very campy, and he mentioned modeling for Dalí and I said, “What? Were you enlisted by Amanda Lear?” And he said, “Yeah, it was complete bullshit. I went up to their suite. There was Dalí sitting in the far corner. But it was all about Gala, his wife. She had me stand on a desk and strip down to my BVDs and there were all these hangers-on milling around being fabulous but Gala was the only one who was concentrated on the model, the angel. And she goes, ‘Why don’t you masturbate, dear boy?’ ” He was creeped out by the whole thing. He said, “I ain’t jacking off for you, lady!” And so he got down and put his clothes back on and said fuck you to everybody. And I said, “Did you even get paid?” He goes, “No! It was supposed to be fifty bucks, but I wasn’t going to jack off for fifty bucks for this old bag.” And that was the thing: all this modeling for Dalí was about Gala’s voyeurism. Because he was … I don’t know what he was.

You’re such a good observer even though you’re young and starstruck. Like with Andy Warhol, at one point you say, “I don’t think he knows he’s Andy Warhol.” I noticed that he just deflected everything, like it was all about you. He just projected out. And I thought, That’s it! He just removes the Warhol from Warhol. I mean he never was given to reflecting on his past, or even his present, he was just like an antenna or something, a receiver. I can really hear him delivering these lines. Like when you say you want to paint like Balthus. And he says, What a good idea. And yells to Ronnie Cutrone, “Hey, Ronnie! He’s trying to paint like Balthus. Can we do that, too?” “Yeah, sure, Andy.” And his eyes lit up and it looked real. You know, it’s terrible being twenty: you’re condescended to, and you’re going to be something, but you aren’t anything yet. It’s like, Yeah, yeah, yeah, you’ll probably wind up back in Des Moines working for your dad’s garage-door company or something. Then you meet a guy like Andy, who’s just like, whatever you’re doing is so much better than what he’s doing. To come across somebody who was that much of a superstar who was also that ... it wasn’t even self-effacing, it was so—like David Hockney always acted like we were peers, which was so generous—but with Warhol it wasn’t even that. He wasn’t even there. Hockney is one of the people who comes off the best. And you just met him randomly in a bookstore, right? What actually happened was I was with a friend and I said, “I had a dream about David Hockney last night,” and I told him the dream. And then he said, “Hey, look, there’s your dream come true.” And I said, “Oh, fuck!” He said, “Well, go on, tell him you had a dream about him.” So I did. And that kind of tweaked his interest. He said, “Hmmm, you did, huh?” He was great. But it was also that thing of being a cute straight boy in a gay world. It’s a balancing act. Because you don’t want to be a cocktease, but I loved and admired these people, and my entrée was the way I looked, so you had to step carefully. And I could completely understand their point of view too, because I’ve certainly been on the other end of it, where you’re enamored of some young beauty. I was also aware that some people were clearly not nice to me. They would just think, You’re beautiful, therefore you’re stupid. And I kind of hate you but I want to fuck you. So there was a double edge to the whole deal. But you were willing to play that up, to a certain point. It was funny, when I got to New York, androgyny was really desirable. David Bowie was beautiful. There were all these beautiful English rock stars. And sometime in the ’70s it changed, and a pretty boy was no longer the number one thing. You could see it on Christopher Street. Suddenly there were guys dressed like cops, and burly guys, and muscle guys and gym guys. Like when I grew up, I was a guy who looked like a sissy, and then suddenly for a few shining moments it was like, Oh! Sissy is in!

Your paintings are figurative and representational, but you started out enamored of De Kooning and abstraction. When did that shift occur? I spent two years trying to paint like an Abstract Expressionist, and I could get nice-looking paintings, but I knew they were fake. I knew they weren’t made the way De Kooning and Yves Klein made theirs. I thought, You could do this for the rest of your life and you’ll just be a phony. I wanted to try to do something that I didn’t already know how to do, so I could grow. Trying to paint the human figure, I felt a connection, because it engages you and you make mistakes. And then as you get better, you also get smarter, and you realize you’ve conquered some limitations, but your vision always exceeds your grasp. I don’t find that frustrating. I find it reassuring—that it just keeps going I wanted to tell stories in my pictures, I wanted to create worlds that people could escape into. I love Alfred Hitchcock’s movies, and I noticed that when they open, it’s often an establishing shot, like a town square with cabs going by. And nothing’s happened yet. It’s like picture-postcard perfect, except it’s not. So what’s telling you that it’s not, besides the fact that you’re watching a Hitchcock movie? I started asking myself, How do you put menace in a landscape? How do you paint something really beautiful that’s got a subtext of sorrow? So how did you solve that? I remember in 1981, in my first show, where this book ends, I did a painting called The Waiting. I was really into ghosts. And I’d had some ghostly experiences, which miraculously vanished when I quit drinking. But I had the shining, as they say. It happened maybe six times in my younger life, if there was a ghost around it would find me, because I was so jangly and out-there that the ghost thought, Ah, kindred spirit. So I thought, How do you paint a ghost story? And initially I would do an interior and put, like, a white shape in it, that’s the ghost, but it looks kind of funny, it looks modernist because the ghost looks like an Arp shape. Then I tried just a blurry little light in a room, which is in my experience what a ghost has looked like. But that looked cheesy. So then I thought, Can you just put the ghost in the room because you meant it to be there? So I did this painting called The Waiting, which was an empty hotel room. And this woman who worked at the gallery looked at The Waiting and said, “This is my favorite painting in the show.” And I said, “Oh, yeah, how come?” And she said, “Well, this will sound weird, but my husband and I were in Ireland and we stayed at this inn and it's haunted and I talked to the ghost,” and she told me this ghost story. And I said, “And that makes you think of it?” And she said, “Yeah, is that stupid?” I said, “That is so great, because that is exactly what I was hoping to trigger.” That was early on, so I was thinking, If you can fuck with people’s subconscious somehow, in a seemingly innocuous picture, that would really be something. That became a challenge: subtlety. How do you make something that is seemingly a cliché but has this undercurrent that the viewer will experience but not know why? Painting’s got that power, but it’s nothing you can formalize.

There are a few story arcs in this book. There’s a downward arc of substance abuse and self-destruction. How did it feel, reading that in your own words? Well, I didn’t notice it so much the first time, but the last time I read it, which was the sixth or seventh because of all this editing you have to do, I just thought, Ugh, would you please? Just don’t do it again. You’re witnessing yourself heading for disaster. Yeah, stop it already. It’s not going to be different. It’s going to be exactly the same. But I had this romantic delusion. Most of my heroes were alcoholics or drug addicts. Like Fitzgerald—I just assumed that his excess somehow released the Muses. And initially you have a great night out and it’s hilarious and euphoric and you’re kind of getting away with it. And when you’re young you just think things are going to get better, and there comes a point in your twenties where it starts getting worse. And I remember thinking, This doesn’t feel the way I thought it was going to. I didn’t think I was old enough to be an alcoholic. But I thought, Something feels horribly wrong. Did Fitzgerald feel horribly wrong? Did Kerouac? You describe going to the Roxy Music after-party with Bryan Ferry, and it’s unbelievably glamorous. And then there’s just like a snap and you wake up lying on the floor of a warehouse in Harlem. I went from jealousy to pity in two pages. When I went on a bender for five or ten days, it would just bring me near death. I’d be horribly, toxically sick. But also the kind of abject depression that comes with it. Like I’d killed myself. Four days later, I’d start coming back to life and get my spirits back. But then I’d just do it all again. It was just a roller coaster, up and down. And at the end of the book I think it just starts getting … I sensed, This guy’s dying inside. In the diaries you wrote, “The trick is to live as if you’re going to die, and then not die.” Which I feel like you’ve now done. I think I wrote that when Nancy Spungen died. The thing about the punk ethos was, self-destruction was totally in, but if you follow it to its natural conclusion then you’re not here anymore, and I definitely wanted to still be here. I’ve never been a nihilist. There is a kind of thrill in treating yourself as if you have no worth, to throw yourself away, which I did, hundreds and hundreds of times. But you can’t do that forever.