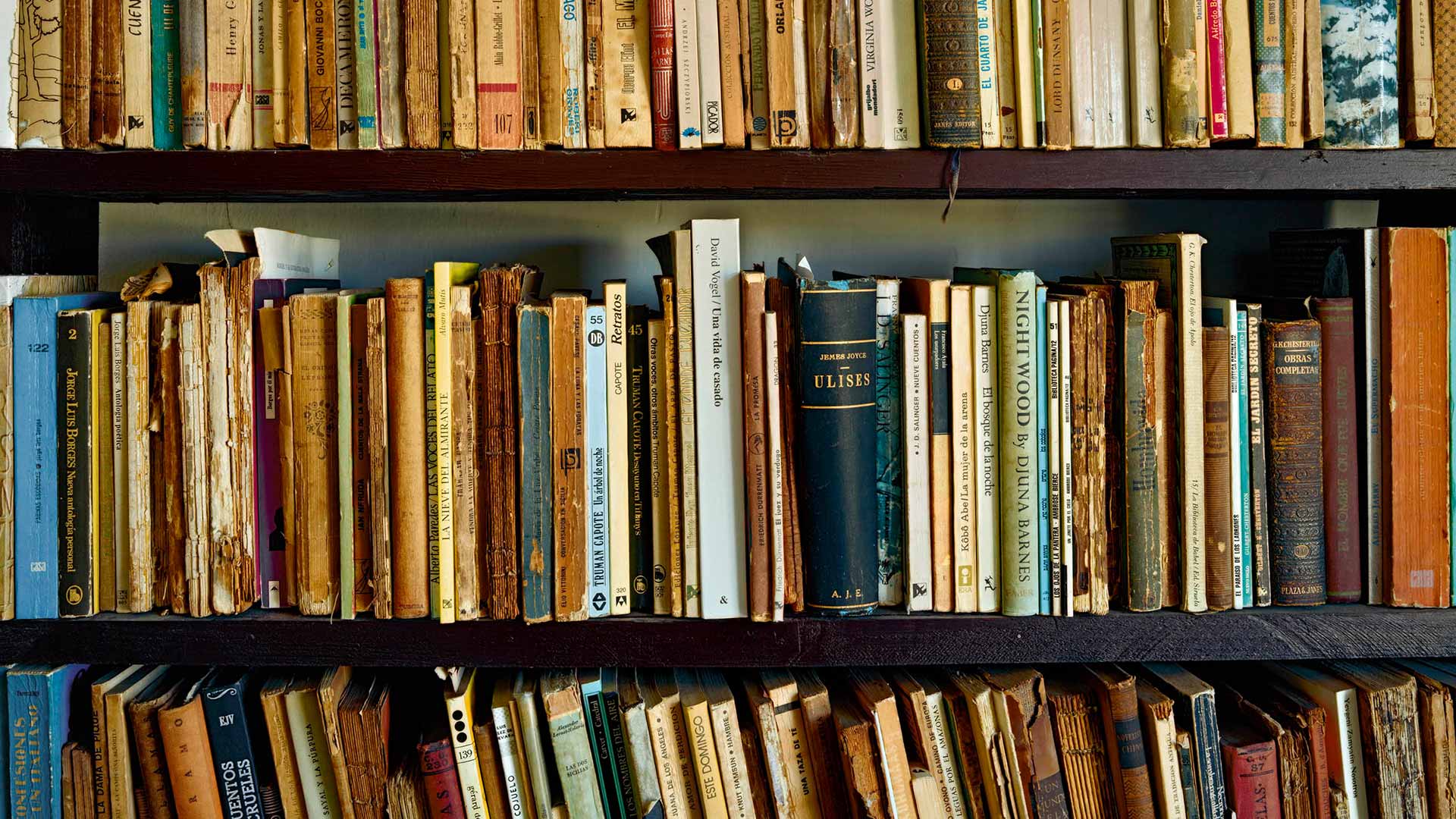

When my marriage of sixteen years ended, I had to find a place to live and I moved in with a friend. My friend is a well-known writer and he owns a large brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn, a neighborhood that looks like Sesame Street. It was October when this happened and the days were quickly getting shorter and the very quickness generated a sense of anxiety, that there wasn’t enough time, that things were sliding away. My friend was also going through troubles. He had designed the house with a woman in whose company he had planned to spend the rest of life. They had put a nursery on the second floor, and a large, high-powered washer/dryer next to this because of all the dirty clothes they expected. But the woman left him. The confusion and pain of it had been so great that he began traveling around, trying to spend as little time in the house as possible. The house is beautiful. It is from the early 1900s and my friend had bought it gutted—there had been no floors, only the front and back walls; standing in the basement of the house and looking up had generated in him an eerie feeling toward this structure that looked like a house from the outside but was something else and alien within. When the woman told him she wanted to end the relationship, he told her to take whatever she wanted. I arrived one morning and was met by my friend’s mother—my friend was out of the country. The house, which is five stories, had once been full of the couple’s furniture. Now it was mostly empty. There were sofas in the living room and there was a dining table in the kitchen, but otherwise the house was empty room after empty room, white walls and shiny hardwood floors. Walking around, I opened closets and saw what remains of a relationship when pain causes one to hurry away: bags of clothes, childhood photos, mismatched shoes. My friend remained out of the country and those weeks when I was alone in the house were some of the loneliest of my life. To me, fall’s cold and darkness have always suggested intimacy, the leaning in to be warmer and to see more clearly. Now there was no intimacy, only aloneness. I tried to stay out of the house as much as possible. I would leave early in the morning to go to work and try to get home late at night. Even now when I recall climbing the stairs to my bedroom on the second floor, my hand on the wooden rail, the house so silent that a dropped coin could be heard throughout the building, I get clammy. * * * Two years have passed since then. My friend is still rarely in the house. He has a sick uncle in Vienna and a sick father living just outside Los Angeles, and he often finds an excuse to go to Mexico. I also travel regularly and there have been extended periods of five or six weeks when we have overlapped in the house for only two or three days. The house is much more full of life, though. Every room has furniture and my friend has rented out work space to other writers. On the top floor is where a Booker Prize–winner writes. Just down the hall from him are two other fiction writers. Regularly there are journalists doing interviews in the living room, and photo shoots in the back garden. In the living room is a foosball table. This table, as much as the activity, makes the house feel like a tech startup. I rent two rooms in the house, the nursery and a small bedroom beside it. At some point, I told a colleague of mine that I rent rooms in someone’s house. The colleague looked at me with pity. She asked why I didn’t rent my own apartment. And then when I told her about the house, she told me that she had heard of it, that it was spoken about in literary parties, and that it seemed like a wonderful place to live. * * * There are books everywhere in the house. In the living room are floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. On the floor of the kitchen are stacks of books. On the steps to the third floor is an odd collection of biographies of heavy-metal performers. When all the writers are in the house working, there is a sense of hushed concentration. The energy is self-perpetuating. Maybe the writers are afraid to appear lazy and so, during lunch, they come down to the kitchen, eat quickly, and hurry back to their laptops. The only person who doesn’t appear to be working is me. I, too, am a writer in that I have published novels and short stories. I am not a writer in that I am not actually writing anything new. I have been trying to understand why. The nursery is my office. I rarely go in there. I mostly use the sofa in that room to pile my laundry. And the desk is where I go to sign checks. When I have made it to the desk, my brain freezes. When I think of sitting there, I get frightened. Very recently, I have begun to write. I do this in my bed. My bed is covered in clothes. There is a chair nearby with more clothes. The floor has books and papers. On top of the dresser is a clutter of pens, coins, receipts. Being inside this mess, I feel comfortable. I feel safe. When I lie here in bed writing I feel as though I am talking only to myself. When I go to my desk, I feel as though I am revealing myself to others, and there, in the dreamed-of nursery, the shame of having had a marriage end, of having failed, becomes so clear that I don’t think anything I have to say is worth hearing. And so I lie in bed and type these words. Akhil Sharma is the author of the novels An Obedient Father and Family Life. He has received the Pen Hemingway Award and the International Dublin Literary Prize, among other awards. His short stories have appeared in The New Yorker and The Paris Review.

我們將進行通訊系統升級,請在此登記Aesop香港官方WhatsApp,以保障資料安全並享個人化服務。了解更多

購物車

容量

數量

我們提供產品寄送服務範圍包括中國香港特別行政區與中國澳門特別行政區。

所有價格均以港幣計算

小計