Listen carefully. What makes ‘good’ conversation, and how does it differ from its insufferable sibling, small talk? Perhaps it’s the same set of conditions that gives anything—food, wine, a signature dance move—its elusive ‘goodness’: practice, intention, and a touch of talent. Self-professed ‘quotamaniac’, interviewer and educator Paul Holdengräber has built a career on conversing, thanks to a knack for picking the brains of brilliant individuals. His latest endeavour, The Quarantine Tapes, chronicles shifting paradigms in the age of social distancing. Each day, Holdengräber calls a guest for a brief discussion on how they are experiencing the present moment—the subsequent dialogue, often heard over a dusty phone line, is typically sincere and thought-provoking. It can also be seen as a blueprint for insipid interlocutors hoping to become tantalising conversationalists. Start from the beginning, or pick an episode at random—all are worth an eavesdrop.

Order a change of tune. Of all the assaults on modern ears, a thoughtlessly curated restaurant soundtrack, endured at diabolical decibels, certainly rates among the worst. To complement a delicious meal, striking the right chord requires hitting three keys: track choice, acoustics and volume. First, a thirteen-minute drum solo is unbearable at the table, as is the chef’s workout playlist or, say, arena rock. Next, the current trend of minimalist interior design in dining rooms often leads to a cacophony of jumbled sounds bouncing off the walls: a few discreet acoustic panels here and there may be in order. Finally, volume is not rocket science—a good rule of thumb: let the them eat cake and hear each other’s opinion of it. If all else fails, take charge: when revered musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto became fed up with the playlists at an eatery that kept him otherwise well fed, he created one for them.

Contemplate the intricacies of intimacy. Lee Mingwei brings his audiences closer to one of the most basic, yet most vital, purposes of art: to help people feel. Born in Taiwan and based in Paris, the artist creates participatory pieces and installations that combine ritual, poetry and strangers—the effect is reflective and lingering. As you wait for his work to appear in your local gallery or museum, look through his past projects—many of which function as intimate guides to understanding oneself and humanity.

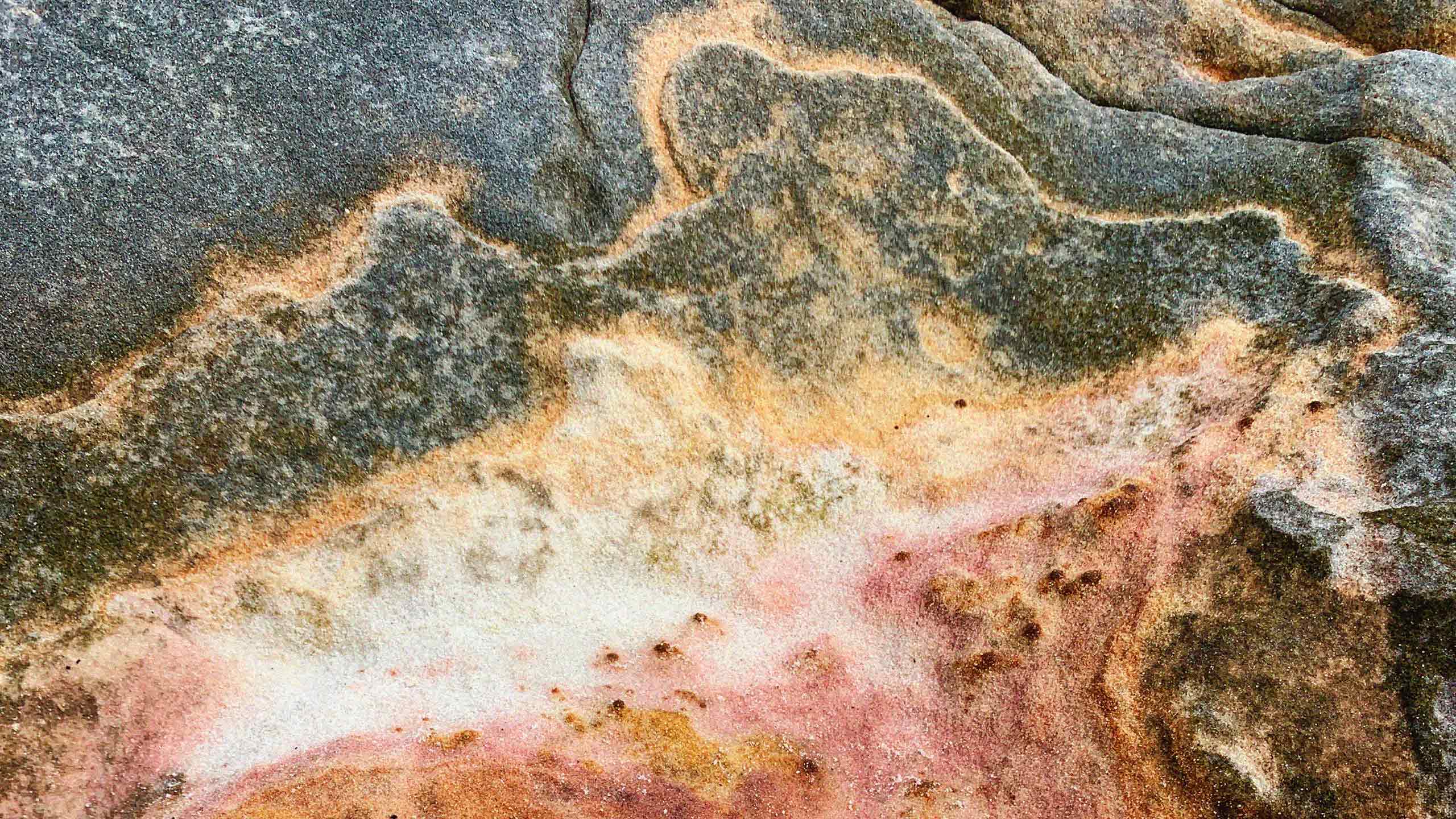

Bask in a bouquet of the senses. ‘Each day, we breathe about 23,040 times and move around 438 cubic feet of air. It takes us about five seconds to breathe—two seconds to inhale and three seconds to exhale—and, in that time, molecules of odor flood through our systems. ... Smells coat us, swirl around us, enter our bodies, emanate from us. We live in a constant wash of them. Still, when we try to describe a smell, words fail us like the fabrications they are…’ So writes poet, pilot, naturalist, journalist, essayist, and explorer Diane Ackerman, in her book A Natural History of the Senses—an opulent union of scientific history, poetry and trivia. The volume is worth reading for the chapter on scent alone—upon finishing that, however, the urge to devour the others will be hard to resist.

Consider your seat at the table. Tunde Wey uses Nigerian cuisine to interrogate colonialism, capitalism and racism, but the artist, cook and writer is less interested in what is served at the table, than in what is learned from it. Provocative, stimulating and delivered without fuss, Wey’s projects include a food stall demonstrating the greater earning power of white people, a dinner series introducing US citizens to immigrants in the hopes of sparking empathy, and a fight against gentrification using hot chicken. There are few culinary critics whose work is worth its weight in salt—Wey is one of those..